Partager

Jim’s Journal

1 août , 2023

By Jazmine Aldrich

One of the great pleasures of archives is diving into the past and discovering new perspectives. I recently stumbled upon James ‘Jim’ Wark’s journal which was written to his family in Sherbrooke as he travelled from Quebec to England on his way to the European front during the First World War.

James Howard Wark was born in Sherbrooke on August 1st, 1897 to John G. Wark (1855-1925) and Catherine Fraser (1857-1938). As a young man, Jim, as he was known colloquially, served for a brief period with the Canadian Expeditionary Force during WWI. He enlisted with 1st Depot Battalion, 1st Quebec Regiment in May 1918 at an enlistment office in Montreal and was quickly on his way to England, arriving in mid-July.

His journal begins on Wednesday, June 26, 1918: Jim describes waking up at 4:00 AM, forming up at the parade grounds, traveling by train to the ship they would travel on, and setting sail. What becomes clear through Jim’s journal entries is that he was optimistic and earnest in the face of the unknown awaiting him at the end of his Atlantic crossing. Of their first evening aboard the sea vessel, Jim writes that “After supper we went on deck and watched the sun-set. It was beautiful. We could see a great many porpoises coming to the surface.”

Despite his grim destination, Jim’s journal entries reflect the thoughts of a 20-year-old man experiencing his first overseas trip. He describes the journey as being “most interesting. It wakes you up to the fact of how little you do know and how much there is to be learned.”

The fun didn’t stop when the military vessel anchored in Halifax harbour to await others destined for their convoy. On July 2nd, 1918, Jim reports that “About 20 nurses came on here this A.M. too. Some real nice ones among them. We had lots of fun with a bunch who were at the wharf to see the others off. One of them gave my side-kick a doll and he is carrying it all around with him now. You should see the men look at him.”

Interspersed with his comments about the fine weather, delicious food, and diverting entertainment are references to the stark reality that drew closer with each passing day. The contrast in his two realities is most evident in this entry from July 10th, 1918:

“This has been the finest and best day we have had on the water yet. The sea was just as smooth and calm as the St. Francis on a fine day, not a ripple on it only an easy swell which gave the old boat a nice see-saw motion. We saw hundreds of porpoises today swimming right in among the boats. I guess we are getting into the danger zone now because the cruiser is going back and forth across our front on the lookout for danger signs. I heard this morning that we are only about [censored] miles from England. Tomorrow they expect to meet the convoy which is to escort us in. This afternoon they sighted a whale but I missed it.”

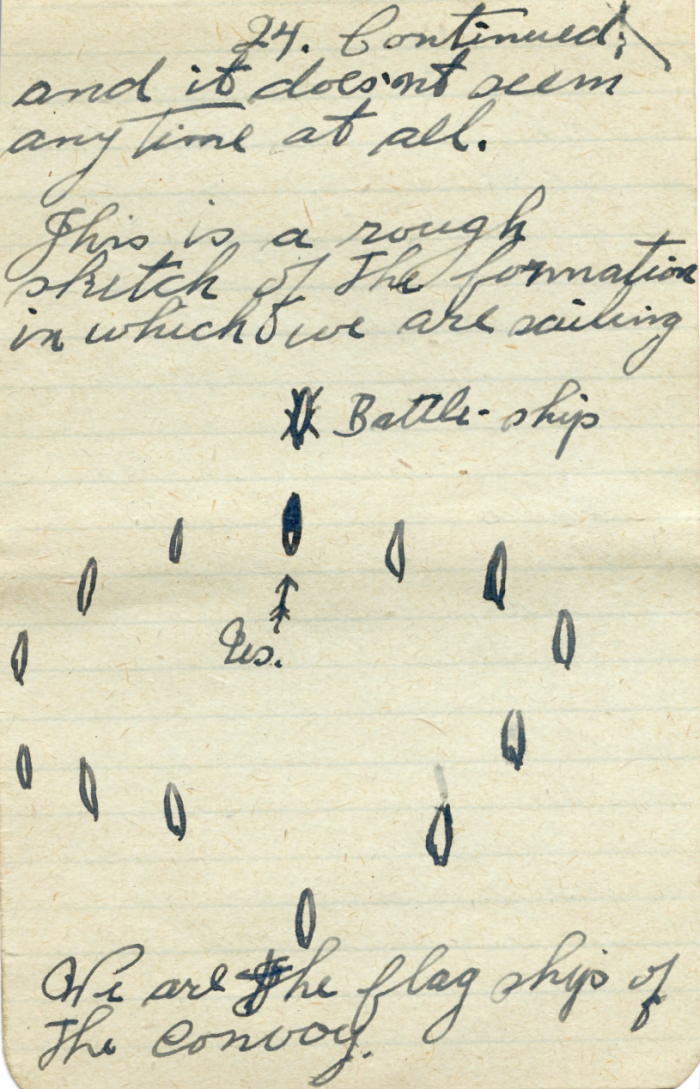

Another reminder of Jim’s wartime reality are the passages struck out with a black marker, indicating censorship of sensitive military information. References to the ship’s relative location and speed are censored. Postal censorship was common practice during the First World War to avoid enemy interception.

As their vessel inched closer to England, they took greater precautions to avoid detection by enemy ships: “They put us off the deck now at 7:30 sea-time, that would be about 5 at home. After that there are no lights showing anywhere on deck. The penalty for showing any light after dark on the war zone is death.”

Though the threat of death lay over his head, the tone of Jim’s entries remained cheery until the end of his journey; on July 12th, 1918, he vowed that “If I ever get the chance I will take this trip again in peace time on a big boat, it is certainly great, something one will never forget.” Jim’s journal entries end when he arrives in England on Monday, July 14th, 1918; fortunately, his story did not end there.

Upon arrival in England, Jim was placed in a segregated camp for CEF recruits as part of a quarantine set up in response to the Spanish flu. This quarantine lasted 28 days and, along with other precautions taken in response to influenza, drastically lengthened the training period for Canadian recruits. As a result, he would complete his training as the war was drawing to an end and would not reach continental Europe during his time overseas. Jim was discharged from his duties in Montreal, demobilization being given as the reason for his discharge. He lived to be 72 years old; he married Florence Bryant (1901-1993), of the J.H. Bryant bottling company family and together, they had two daughters: Catherine (1929-2009) and Barbara (b. 1930).

Jim’s journal is digitized and available online. If you are interested in reading this fascinating tale, please visit the Eastern Townships Archives Portal: https://townshipsarchives.ca/jim-wark-wwi-journal.

Crédit photo: : P234 Wark family (Sherbrooke) fonds

A page of Jim’s wartime journal showing the convoy’s sailing formation when nearing England. Jim indicates that his is the flagship of the convoy, following a battle ship. Twelve other ships make up the diamond-like formation.

Crédit photo: : P234 Wark family (Sherbrooke) fonds

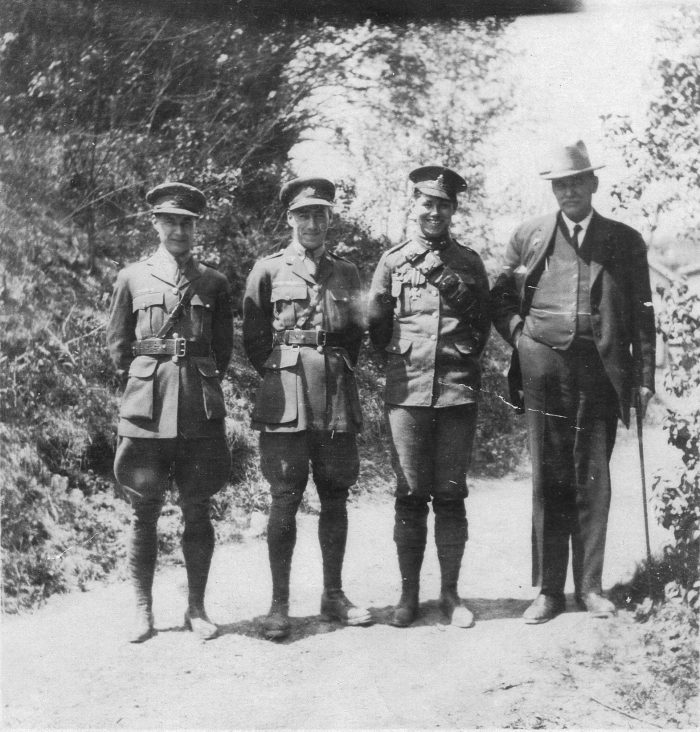

James ‘Jim’ Wark (far right), pictured in his military uniform with fellow soldiers at Ripon Camp in North Yorkshire, England on March 5, 1919.

Crédit photo: : P234 Wark family (Sherbrooke) fonds

(left to right) Albert Bryant, Guy Bryant, Clifford Bryant, and John Henry Bryant during the First World War.